Passion For Genealogy is reader supported. When you use and buy through links on this site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Table of Contents

GENEALOGY MILITARY RESEARCH BEGINS

This is a true genealogy military research story. Come along with me on my quest to find ancestry information on this unsung hero of The Great War.

As we enter yet another year with the pandemic, I am reminded of my late husband’s father, Lester Lawrence Wells who dealt as a young man with the uncertainties of infectious diseases and death. I had never met Lester as he passed away years before I met my husband. His family spoke of him kindly as a serious, good hearted man. He rarely discussed his time as a medic in World War l. Years after his death some of his papers resurfaced, including old enlistment records, letters written to his parents while serving in the military. We also located copies of old army newspapers like the Trench and Camp. This information was a gold mine in learning more about the Great War and one particular young man in our family who gave up his youth to answer the call.

LIFE ON THE FARM

Lester was born August 27, 1897 in Paulding, Ohio. He was the fourth child of a family of ten. His father, Albert Harper was a small dirt farmer trying to make ends meet without much success. When Lester was in his early teens, the family moved to the small farming community of Dryden, Michigan in hopes to better their lives. All the children were required to work the farm with the exception of school days.

Lester excelled in his studies and was also accomplished in sports. In high school he played the role of Abraham Lincoln in the annual school play. Due to his size and acting abilities, his classmates and later acquaintances nicknamed him “Abe.” After graduating from high school in 1915, he later attended college and worked as a laborer to pay for his education and help out the family. He enjoyed attending school and had ambitions to become a minister, but those dreams soon came to an end.

AMERICA ENTERS THE WAR

On April 6, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson declared that the United States would join its allies—Great Britain, France, and Russia—to fight in World War I. After remaining neutral for three years, Wilson had no choice but to enter the war after Germany sank U.S. merchant ships killing numerous Americans. After Congress approved Wilson’s request for entering the war, the volunteer turnout was much smaller than the president expected. Knowing that he could not put together an army with so few individuals, Congress passed the Selective Service Act. On May 18, 1917, Wilson issued a Presidential Proclamation which required all men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register at their local draft board for a draft lottery.

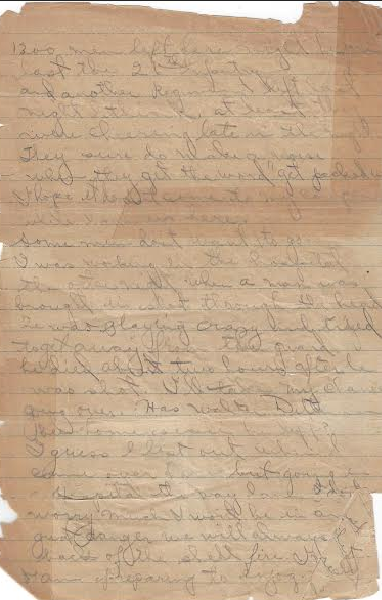

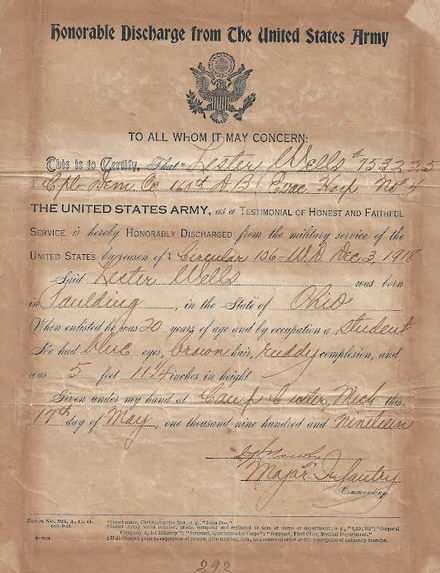

Lester made his way to the draft board in Detroit and on September 28, 1917 he enlisted. His enlistment record stated that he was 20 years old, had blue eyes, brown hair, and ruddy complexion and was 5’ 11 ¼” tall. His occupation was listed as student. After enlistment, he was sent to the Columbus Barracks, later renamed Fort Hayes in Ohio for basic training. It is unclear whether or not Lester chose his destination as a future medic, but following basic training he was assigned to Evacuation Hospital No.4 and was soon promoted to Corporal on December 5, 1917. It appears by this period that he must have been aware that he would soon be leaving for the battle front.

LETTER FROM OVERSEAS

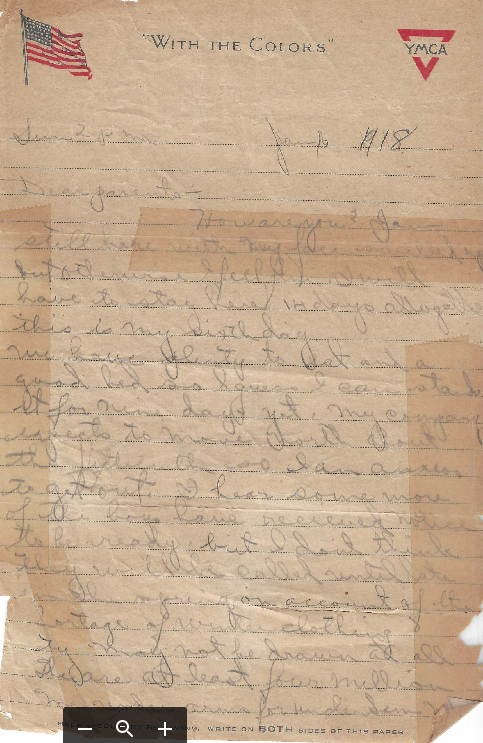

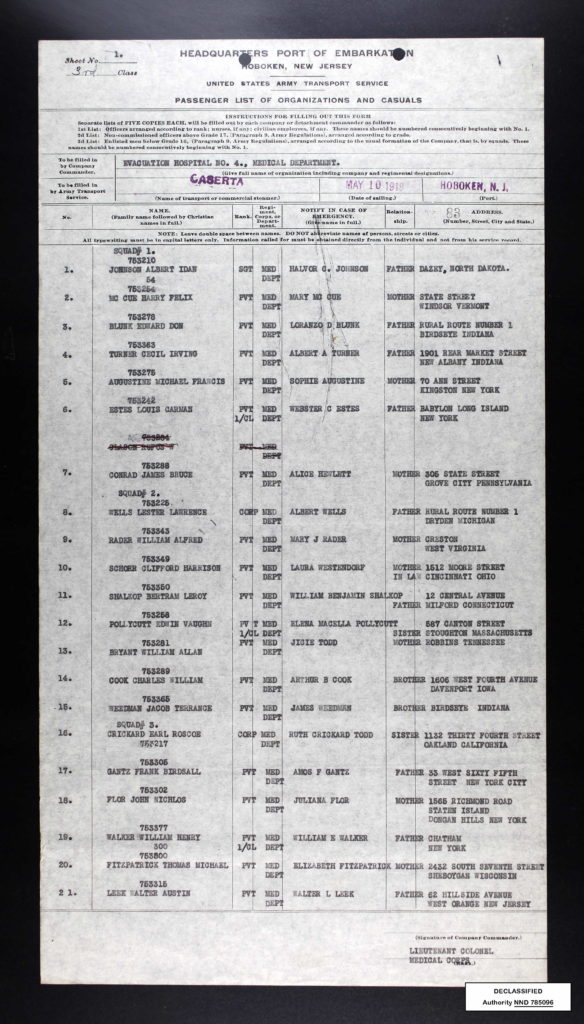

In one of his letters to his parents, dated January 6, 1918 he writes about his concerns about being sent overseas while he is recuperating from the mumps. He writes:

“My company expects to move north about the fifteenth so I am anxious to get out. I hear some more of the boys have received notice to be ready but I don’t think they will be called until late in the spring on account of the shortage of winter clothing. There are at least four million men under arms for Uncle Sam now. 1,300 men left here night before last. The 26th Infantry and another Regiment left last night I think. At least they were cheering late in the night. They sure do make a noise when they the get word ‘get packed up.’

I hope it doesn’t come to my company while I am in here. Some men don’t want to go. I was working in the hospital the other night when a man was brought in shot through the head. He was playing crazy and tried to get away from the guard. He died about two hours after he was shot. I’ll take my chances going over.”

EVACUATION HOSPITALS

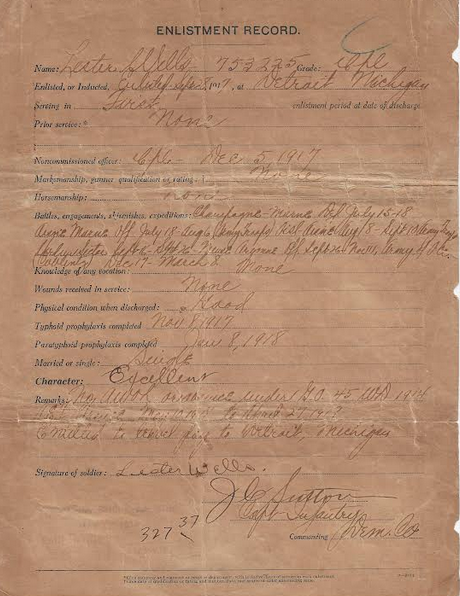

On May 10, 1918, the troops of Evacuation Hospital No.4 set sail for France on the newly chartered ship The Caserta. The Caserta was constructed in 1904 in the city of Caserta, Italy and had been sold several times over the years. By the time the American troops boarded her she had sailed plenty of missions and was a little worse for wear. The troops nicknamed her the “cattle boat” and it was safe to assume that she was no luxury liner.

Evacuation hospitals were a fairly new concept in 1917. They were originally conceived as a mobile medical facility that could support the infantry division field hospital across the Western Front of France.

Fighting in World War One was unlike other wars. Trenches dominated much of the battlefield; and as trenches were so confined there was a distinct lack of sanitation along with fresh water. Soldiers would have to be circulated periodically to be cleaned and deloused. Diseases such as dysentery, pneumonia, and tuberculosis were at a high as antibiotics had not yet been invented. During World War I, disease awareness and prevention became more prevalent than civilian life. The top doctors and researchers were utilized in the military not at home. Although evacuation hospitals were not as fully equipped as large hospitals they were still able to do surgical procedures along with treating flesh wounds and other illnesses.

By the early 20th century, new medical advancements such as x-ray machines, blood transfusions, intravenous fluids, and on-site laboratories were used, helping more soldiers to survive then in previous wars. Protocol on the field was that as the wounded or sick entered the Evacuation Hospital they were either treated or transported to a more equipped facility as was determined by medical personnel.

WESTERN FRONT

Soon after arriving in the port of St. Nazaire, France, Evacuation Hospital No. 4 began preparing for setup. Location was the key to success. The army surgeon or assistant would make the determination as the best spot for their needs. In most cases the temporary facility would be placed near a railroad and/or near a town closest to the battle field and hopefully out of harm’s way. Transportation was a necessity so good roads were needed for ambulance and supply needs. Tents were set up unless an empty building was available. This process was repeated over and over. To move the units to each site was a huge undertaking. The average evacuation hospital would take approximately 90 3-ton trucks or 30 rail cars to move the entire entity from place to place.

Lester’s war record lists the battles he had engaged. He was behind the lines working tirelessly during war events such as the Champagne Marne Defensive, Aisne Marne Offensive, Verdun Sector, and the Meuse Argonne Offensive. These battles ranged from July 12, 1918 through November 11, 1918. According to the U.S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History, “During the Aisne-Marne operation Evacuation Hospital No. 4 received patients from 5 divisions, and from September 26 to November 1918, it received patients from 11 divisions.”

Without a doubt being a part of this Corp was intensely serious business. It is hard to imagine a young man coping with the uncertainty of his own demise, let alone attending to hundreds of wounded who in many cases would never survive. At 11am of the 11 day of the 11 month of 1918, World War I ended with a signed armistice between Allies (Great Britain and France) and Germany. As Germany was facing a loss of power and threats of invasion, the armistice ended one of the world’s most bloody conflicts in history.

YEARS AFTER THE WAR

After the Armistice was signed, Lester continued his role as a medic during the Army of Occupation. His division moved to the city of Koblenz in Germany located at the junction of the Rhine and Moselle rivers. Three hotels and a school house allotted their space to become the next Evacuation Hospital No. 4. Since the war had come to an end the medic’s tasks were now limited to ear, nose, throat, optical service, and other limited medical services. Later Lester would comment to his son that he enjoyed getting to know the German people and their customs during his short period there.

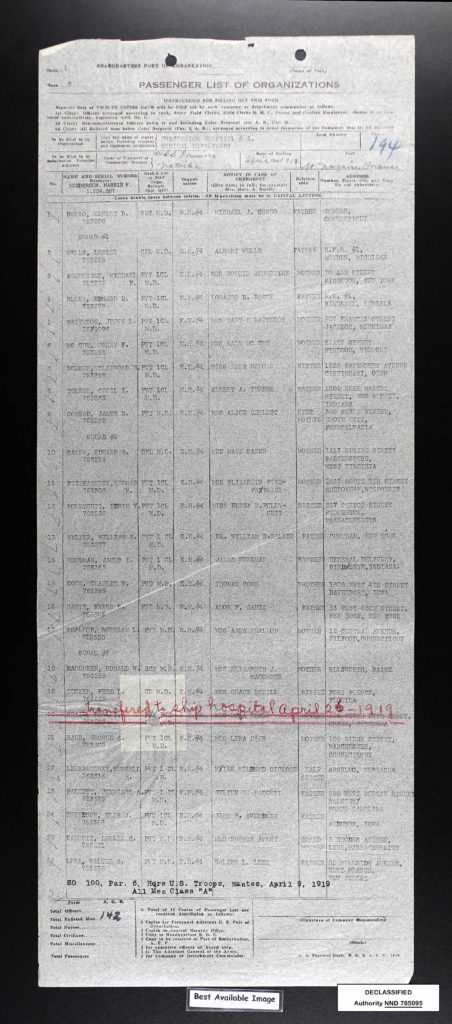

On April 27, 1919, he departed France on the ship the Princess Matoika and was later honorably discharged from service on May 17, 1919. For his service, he was awarded the World War I Victory button and medal, Champagne-Marne Battle Clasp, Battle Clasp with Meuse-Argonne, Clasp with Oise-Aisne and Army of Occupation medal.

RETURNING HOME

Lester returned home to Dryden, Michigan, yet he did not pick up his studies again or become a minister. At age 25 he married a young widow with three young boys and over the next few years they produced three additional sons.

Over the course of forty years, he worked in road and bridge construction. After retirement he became a consultant and board member of a large bridge building company. He passed away on July 23, 1969, a true unsung hero of the Great War.

GENEALOGY MILITARY RESEARCH

I hope you enjoyed my recent story on genealogy military research. If you liked this article you may want to read my other genealogy military work found here.